Anarchy

Anarchy is the form of societal organization and government which is advocated by Anarchism. In anarchy, the institutions viewed by anarchists as maintaining unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, including the nation-state and capitalism, in favour of a stateless society of voluntary free association.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

Anarchy is primarily advocated by anarchists who propose replacing the state with voluntary institutions. These institutions or free associations are generally modeled to represent concepts such as community and economic self-reliance, interdependence, or individualism. In simple terms anarchy means 'without rulers' or 'without authority' in which there is no rule by group or tyrant, rather instead by an individual upon themselves or by the people entirely. It is non-coercive.

Definition

As a concept, anarchy is commonly defined by what it excludes.[1] Etymologically, anarchy is derived from the Greek: αναρχία, romanized: anarkhia; where "αν" ("an") means "without" and "αρχία" ("arkhia") means "ruler".[2] Therefore, the etymological root of anarchy means 'the absence of rulers.'[3]

While the etymological root anarchy means 'without rulers', anarchy itself refers to a stateless society without unnecessary coercion and hierarchy.[4] Anarchy is thus defined in direct contrast to the State,[5] an institution that claims a monopoly on violence over a given territory.[6] Anarchists such as Errico Malatesta have also defined anarchy more precisely as a society without unnecessary authority,[7] or hierarchy.[8]

Anarchy is also sometimes used derogatorily to mean chaos or social disorder with no government,[9] reflecting the state of nature as depicted by Thomas Hobbes.[10] However, many anarchists have stressed that they do not object to government, but rather the hierarchical forms of government associated of the nation state.[11] Sociologist Francis Dupuis-Déri has described chaos as a "degenerate form of anarchy", in which there is an absence, not just of rulers, but of any kind of political organization.[12] He contrasts the "rule of all" under anarchy with the "rule of none" under chaos.[13]

Overview

Anthropology

Peter Leeson examined a variety of institutions of private law enforcement developed in anarchic situations by eighteenth century pirates, preliterate tribesmen, and Californian prison gangs. These groups all adapted different methods of private law enforcement to meet their specific needs and the particulars of their anarchic situation.[14]

International relations

In international relations, anarchy is "the absence of any authority superior to nation-states and capable of arbitrating their disputes and enforcing international law".[15][16]

Anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

|

As a political philosophy, anarchism advocates self-governed societies based on voluntary institutions. These are often described as stateless societies,[17][18][19] although several authors have defined them more specifically as institutions based on non-hierarchical free associations.[20] Anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, or harmful.[18][21] While opposition to the state is central, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition.[22][23] Anarchism also entails opposing unnecessary authority or hierarchical organisation in the conduct of all human relations, including yet not limited to the state system.[24][25][26]

Immanuel Kant

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant treated anarchy in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View as consisting of "Law and Freedom without Force". For Kant, anarchy falls short of being a true civil state because the law is only an "empty recommendation" if force is not included to make this law efficacious. For there to be such a state, force must be included while law and freedom are maintained, a state which Kant calls a republic. Kant identified four kinds of government:[27]

English Civil War and French Revolution

English Civil War (1642–1651)

_-_A_landscape_with_travellers_ambushed_outside_a_small_town.jpg.webp)

Anarchy was one of the issues at the Putney Debates of 1647:

Thomas Rainsborough: "I shall now be a little more free and open with you than I was before. I wish we were all true-hearted, and that we did all carry ourselves with integrity. If I did mistrust you I would not use such asseverations. I think it doth go on mistrust, and things are thought too readily matters of reflection, that were never intended. For my part, as I think, you forgot something that was in my speech, and you do not only yourselves believe that some men believe that the government is never correct, but you hate all men that believe that. And, sir, to say because a man pleads that every man hath a voice by right of nature, that therefore it destroys by the same argument all property – this is to forget the Law of God. That there's a property, the Law of God says it; else why hath God made that law, Thou shalt not steal? I am a poor man, therefore I must be oppressed: if I have no interest in the kingdom, I must suffer by all their laws be they right or wrong. Nay thus: a gentleman lives in a country and hath three or four lordships, as some men have (God knows how they got them); and when a Parliament is called he must be a Parliament-man; and it may be he sees some poor men, they live near this man, he can crush them – I have known an invasion to make sure he hath turned the poor men out of doors; and I would fain know whether the potency of rich men do not this, and so keep them under the greatest tyranny that was ever thought of in the world. And therefore I think that to that it is fully answered: God hath set down that thing as to propriety with this law of his, Thou shalt not steal. And for my part I am against any such thought, and, as for yourselves, I wish you would not make the world believe that we are for anarchy."

Oliver Cromwell: "I know nothing but this, that they that are the most yielding have the greatest wisdom; but really, sir, this is not right as it should be. No man says that you have a mind to anarchy, but that the consequence of this rule tends to anarchy, must end in anarchy; for where is there any bound or limit set if you take away this limit, that men that have no interest but the interest of breathing shall have no voice in elections? Therefore, I am confident on't, we should not be so hot one with another."[28]

As people began to theorize about the English Civil War, anarchy came to be more sharply defined, albeit from differing political perspectives:

- 1656 – James Harrington (The Commonwealth of Oceana) uses anarchy to describe a situation where the people use force to impose a government on an economic base composed of either solitary land ownership (absolute monarchy), or land in the ownership of a few (mixed monarchy). He distinguishes it from commonwealth, the situation when both land ownership and governance shared by the population at large, seeing it as a temporary situation arising from an imbalance between the form of government and the form of property relations.

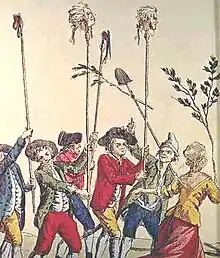

French Revolution (1789–1799)

Thomas Carlyle, Scottish essayist of the Victorian era known foremost for his widely influential work of history, The French Revolution, wrote that the French Revolution was a war against both aristocracy and anarchy:

Meanwhile, we will hate Anarchy as Death, which it is; and the things worse than Anarchy shall be hated more! Surely Peace alone is fruitful. Anarchy is destruction: a burning up, say, of Shams and Insupportabilities; but which leaves Vacancy behind. Know this also, that out of a world of Unwise nothing but an Unwisdom can be made. Arrange it, Constitution-build it, sift it through Ballot-Boxes as thou wilt, it is and remains an Unwisdom,-- the new prey of new quacks and unclean things, the latter end of it slightly better than the beginning. Who can bring a wise thing out of men unwise? Not one. And so Vacancy and general Abolition having come for this France, what can Anarchy do more? Let there be Order, were it under the Soldier's Sword; let there be Peace, that the bounty of the Heavens be not spilt; that what of Wisdom they do send us bring fruit in its season! – It remains to be seen how the quellers of Sansculottism were themselves quelled, and sacred right of Insurrection was blown away by gunpowder: wherewith this singular eventful History called French Revolution ends.[29]

In 1789, Armand, duc d'Aiguillon came before the National Assembly and shared his views on the anarchy:

I may be permitted here to express my personal opinion. I shall no doubt not be accused of not loving liberty, but I know that not all movements of peoples lead to liberty. But I know that great anarchy quickly leads to great exhaustion and that despotism, which is a kind of rest, has almost always been the necessary result of great anarchy. It is therefore much more important than we think to end the disorder under which we suffer. If we can achieve this only through the use of force by authorities, then it would be thoughtless to keep refraining from using such force.[30]

Armand was later exiled because he was viewed as being opposed to the revolution's violent tactics. Professor Chris Bossche commented on the role of anarchy in the revolution:

In The French Revolution, the narrative of increasing anarchy undermined the narrative in which the revolutionaries were striving to create a new social order by writing a constitution.[31]

See also

- Anarchist feminism

- Anomie

- Criticisms of electoral politics

- Libertarian socialism

- List of anarchist organizations

- Outline of anarchism

- Power vacuum

- Rebellion

- Relationship anarchy

- State of nature

- Unorganization

References

- Bell 2020, p. 310.

- Dupuis-Déri 2010, p. 13; Marshall 1993, p. 3.

- Chartier & Van Schoelandt 2020, p. 1; Dupuis-Déri 2010, p. 13; Marshall 1993, pp. 19–20; McKay 2018, pp. 118–119.

- Suissa 2019.

- Amster 2018, p. 15; Bell 2020, p. 310; Boettke & Candela 2020, p. 226; Morris 2020, pp. 39–42; Sensen 2020, p. 99.

- Bell 2020, p. 310; Boettke & Candela 2020, p. 226; Morris 2020, pp. 43–45.

- Marshall 1993, p. 42; McLaughlin 2007, p. 12.

- Amster 2018, p. 23.

- Bell 2020, p. 309; Boettke & Candela 2020, p. 226; Chartier & Van Schoelandt 2020, p. 1.

- Boettke & Candela 2020, p. 226; Morris 2020, pp. 39–40; Sensen 2020, p. 99.

- Suissa 2019"...as many anarchists have stressed, it is not government as such that they find objectionable, but the hierarchical forms of government associated with the nation state".

- Dupuis-Déri 2010, pp. 16–17.

- Dupuis-Déri 2010, pp. 17–18.

- Leeson, Peter (2014). "Pirates, Prisoners, and Preliterates: Anarchic Context and the Private Enforcement of Law" (PDF). European Journal of Law and Economics. 37 (3): 365–379. doi:10.1007/s10657-013-9424-x. S2CID 41552010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- Lechner, Silviya (November 2017). "Anarchy in International Relations". International Studies Association. Oxford University Press: 1–26. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.79. ISBN 978-0-19-084662-6.

- Eckstein, Arthur M.; et al. (8 September 2020). "Anarchy". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1910). "Anarchism". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Crowder, George (2005). "Anarchism". In Craig, Edward (ed.). The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. p. 14-15. ISBN 0-415-32495-5.

- Sheehan, Sean (2003). Anarchism. London: Reaktion Books. p. 85. ISBN 1-86189-169-5.

- Suissa, Judith (2006). Anarchism and Education: a Philosophical Perspective. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 0-415-37194-5.

- Mclaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 59. ISBN 978-0754661962.

- Mclaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 28. ISBN 978-0754661962.

Anarchists do reject the state, as we will see. But to claim that this central aspect of anarchism is definitive is to sell anarchism short.

- Jun, Nathan (September 2009). "Anarchist Philosophy and Working Class Struggle: A Brief History and Commentary". WorkingUSA. 12 (3): 505–519. doi:10.1111/j.1743-4580.2009.00251.x. ISSN 1089-7011.

One common misconception, which has been rehearsed repeatedly by the few Anglo-American philosophers who have bothered to broach the topic ... is that anarchism can be defined solely in terms of opposition to states and governments (p. 507)

- McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. AshGate. p. 1. ISBN 9780754661962.

Authority is defined in terms of the right to exercise social control (as explored in the "sociology of power") and the correlative duty to obey (as explored in the "philosophy of practical reason"). Anarchism is distinguished, philosophically, by its scepticism towards such moral relations – by its questioning of the claims made for such normative power – and, practically, by its challenge to those "authoritative" powers which cannot justify their claims and which are therefore deemed illegitimate or without moral foundation.

- Woodcock, George (1962). Anarchism: A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements. World Publishing Company. p. 9. LCCN 62-12355.

All anarchists deny authority; many of them fight against it.

- Brown, L. Susan (2002). "Anarchism as a Political Philosophy of Existential Individualism: Implications for Feminism". The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism and Anarchism. Black Rose Books Ltd. Publishing. p. 106.

- Louden, Robert B., ed. (2006). Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Cambridge University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-521-67165-1.

- "The Putney Debates, The Forum at the Online Library of Liberty". Source: Sir William Clarke, Puritanism and Liberty, being the Army Debates (1647–9) from the Clarke Manuscripts with Supplementary Documents, selected and edited with an Introduction A.S.P. Woodhouse, foreword by A.D. Lindsay (University of Chicago Press, 1951).

- Thomas Carlyle. The French Revolution.

- "Duke d'Aiguillon". Department of Justice Canada. 2007-11-14. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- "Revolution in Search of Authority". Victorianweb.org. 2001-10-26. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Bibliography

- Amster, Randall (2018). "Anti-Hierarchy". In Franks, Benjamin; Jun, Nathan; Williams, Leonard (eds.). Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Routledge. pp. 15–27. ISBN 978-1-138-92565-6. LCCN 2017044519.

- Bell, Tom W. (2020). "The Forecast for Anarchy". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 309–324. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-22. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Boettke, Peter J.; Candela, Rosolino A. (2020). "The Positive Political Economy of Analytical Anarchism". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 222–234. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-15. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (2020). "Introduction". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 1–12. doi:10.4324/9781315185255. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Dupuis-Déri, Francis (2010). "Anarchy in Political Philosophy". In Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (eds.). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-0-7391-3240-1. LCCN 2009015304.

- Marshall, Peter H. (1993). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana Press. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 1042028128.

- McKay, Iain (2018). "Organisation". In Franks, Benjamin; Jun, Nathan; Williams, Leonard (eds.). Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Routledge. pp. 115–128. ISBN 978-1-138-92565-6. LCCN 2017044519.

- Morris, Christopher W. (2020). "On the Distinction Between State and Anarchy". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 39–52. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-3. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Sensen, Oliver (2020). "On the Distinction Between State and Anarchy". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 99–111. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-7. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Suissa, Judith (1 July 2019). "Education and Non-domination: Reflections from the Radical Tradition". Studies in Philosophy and Education. 38 (4): 359–375. doi:10.1007/s11217-019-09662-3. S2CID 151210357.

Further reading

- Crowe, Jonathan (2020). "Anarchy and Law". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 281–294. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-20. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Davis, Lawrence (2019). "Individual and Community". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 47–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_3. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Gabay, Clive (2010). "What Did the Anarchists Ever Do for Us? Anarchy, Decentralization, and Autonomy at the Seattle Anti-WTO Protests". In Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (eds.). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-7391-3240-1. LCCN 2009015304.

- Gordon, Uri (2010). "Power and Anarchy: In/equality + In/visibility in Autonomous Politics". In Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (eds.). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 39–66. ISBN 978-0-7391-3240-1. LCCN 2009015304.

- Graham, Robert (2019). "Anarchism and the First International". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 325–342. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_19. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Hirshleifer, Jack (1995). "Anarchy and its Breakdown" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 103 (1): 26–52. doi:10.1086/261974. ISSN 1537-534X. S2CID 154997658.

- Huemer, Michael (2020). "The Right Anarchy: Capitalist or Socialist?". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 342–359. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-24. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Levy, Carl (2019). "Anarchism and Cosmopolitanism" (PDF). In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 125–148. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_7. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- McLaughlin, Paul (2020). "Anarchism, Anarchists and Anarchy". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 15–27. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-1. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

- Powell, Benjamin; Stringham, Edward P. (2009). "Public choice and the economic analysis of anarchy: a survey" (PDF). Public Choice. 140 (3–4): 503–538. doi:10.1007/s11127-009-9407-1. ISSN 1573-7101. S2CID 189842170.

- Prichard, Alex (2019). "Freedom". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 71–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_4. hdl:10871/32538. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Newman, Saul (2019). "Postanarchism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 293–304. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_17. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Shannon, Deric (2018). "Economy". In Franks, Benjamin; Jun, Nathan; Williams, Leonard (eds.). Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Routledge. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-1-138-92565-6. LCCN 2017044519.

- Shantz, Jeff; Williams, Dana M. (2013). Anarchy and Society: Reflections on Anarchist Sociology. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004252998. ISBN 978-90-04-21496-5. LCCN 2013033844.

- Tamblyn, Nathan (30 April 2019). "The Common Ground of Law and Anarchism". Liverpool Law Review. 40 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1007/s10991-019-09223-1. S2CID 155131683.

- Taylor, Michael (1982). Community, Anarchy and Liberty. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24621-0. LCCN 82-1173.

- Verter, Mitchell (2010). "The Anarchism of the Other Person". In Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (eds.). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–84. ISBN 978-0-7391-3240-1. LCCN 2009015304.

External links

- Emma Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays

- On the Steppes of Central Asia, by Matt Stone. Online version of book, hosted by Anarchism.net.

- "Who Needs Government? Pirates, Collapsed States, and the Possibility of Anarchy", August 2007 issue of Cato Unbound focusing on Somali anarchy.

- "Historical Examples of Anarchy without Chaos", a list of essays hosted by royhalliday.home.mingspring.com.

- Anarchy Is Order. Principles, propositions and discussions for land and freedom.

- Brandon's Anarchy Page, classic essays and modern discussions. Online since 1994.

- Anarchism Collection from the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress.