Cesária Évora

Cesária Évora GCIH (Portuguese pronunciation: [sɨˈzaɾiɐ ˈɛvuɾɐ]; 27 August 1941 – 17 December 2011) was a Cape Verdean singer known for singing morna, a genre of music from Cape Verde, in her native Cape Verdean Creole. Her songs were often devoted to themes of love, homesickness, nostalgia, and the history of the Cape Verdean people. She was known for her habits of performing barefoot and stopping performances to smoke and drink on stage. Évora's music has received many accolades, including a Grammy Award in 2004, and it has influenced many Cape Verde diaspora musicians as well as American pop singer Madonna. Évora is also known as Cizé, the Barefoot Diva, and the Queen of Morna.

Cesária Évora GCIH | |

|---|---|

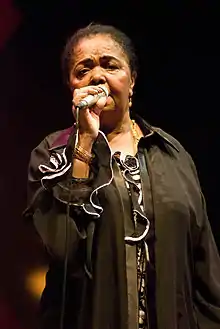

Cesária Évora in São Paulo, 2008 | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Barefoot Diva Cise Queen of Morna |

| Born | 27 August 1941 Mindelo, Portuguese Cape Verde |

| Died | 17 December 2011 (aged 70) São Vicente, Cape Verde |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter |

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active |

|

| Labels |

|

| Website | cesaria-evora |

Growing up in poverty, Évora began her singing career in local bars at age sixteen. She saw relative popularity within Cape Verde over the following years, but she retired from singing when it did not provide her with enough money to care for her children. Évora returned to music in 1985, when she contributed to a women's music anthology album in Portugal. Here, she met French music producer José "Djô" da Silva, who signed Évora to his record label, Lusafrica. She released her debut album, La Diva Aux Pieds Nus, in 1988. Évora saw worldwide success after releasing her fourth and fifth albums: Miss Perfumado (1992) and Cesária (1995). She developed health problems in the late 2000s and died from respiratory failure and hypertension in 2011.

Biography

Early life and music career

Cesária Évora was born on 27 August 1941, in Mindelo, São Vicente (then a colony in Portuguese Cape Verde), as one of seven children. Her father was a violinist; he died while she was still a child. Her mother was a cook who was forced to raise her many children alone following her husband's death.[1][2]: 84 The family's poverty, and that of the entire colony, meant that she received little formal education.[2]: 84 By the time she was ten years old, Évora was moved to an orphanage, as her mother could not support her.[3]

Évora took up singing as a child. When she was 16 years old, she began a romantic relationship with a guitarist who encouraged her to begin performing morna and coladeira, and she began performing in bars.[1][2]: 84 Living in Mindelo provided her with an advantage, as its status as an international port town meant that the city had a large nightlife scene.[4]: 59 Évora began performing across the country alongside Luís Morais, and she became well known among Cape Verdeans. She also developed a following in the Netherlands and in Portugal in the 1950s, but she did not expand or capitalize on these.[1] Évora recorded multiple songs for the radio in the 1960s and released two 45 RPM records.[4]: 59 Her early endeavors in music were challenged by those who believed in traditional gender roles, as music was considered a masculine activity in Cape Verde.[2]: 85 She was further challenged for her mixed race and her social class. To express her frustration, she sometimes wrote songs specifically about these problems, knowing that most of her foreign audience would not understand the lyrics.[2]: 86

Évora had two children, a son and a daughter, about eight years apart. She divorced three times, and was a single mother.[1] She was unable to support her children on the income of a relatively unknown musician,[5] and by the 1970s, Évora decided to retire from music.[1] During these years, she moved back in with her mother.[3] She considered her decade of retirement to be her "dark years".[2]: 87

Return to music and international success

Évora returned to music in 1985, after the Organization of Cape Verdean Women asked her to travel to Portugal and contribute songs for an anthology album of women's music.[1][5] She then met Bana, who asked her to perform in his restaurant in Lisbon.[4]: 59 While performing there in 1987, she was discovered by music producer José "Djô" da Silva, who had her accompany him to Paris.[4]: 59 They had trouble finding a distributor for her music before she eventually partnered with French producer Dominique Buscaï.[2]: 89 She recorded her first album, La Diva Aux Pieds Nus, with da Silva's record label Lusafrica in 1988. She then released Distino di Belita in 1990 and Mar Azul in 1991.[1]

Évora released her fourth album, Miss Perfumado, in 1992. This album was a success, selling hundreds of thousands of copies and giving her large followings in France and Portugal. She began global tours, visiting Brazil, Canada, and the United States, as well as countries in Africa and Europe.[1] Her first major concert success took place this year, when she sold out a performance at the Théâtre de la Ville.[4]: 61 In 1995, after a successful tour in the United State, Évora released her fifth album, Cesária, with the American label Nonesuch Records.[1] This album was more positive in tone than the previous ones,[6] and it earned her international acclaim, including a nomination for a Grammy Award.[7] She released several more albums, each two to three years apart, over the following years.[8]

Évora's ninth album, Voz d'Amor, won a Grammy Award in 2004.[6] Her health began declining the following year when she was diagnosed with heart problems.[3] On her tour in Australia in 2008, she suffered a stroke and had to end the tour early.[8] In 2010, Évora performed a series of concerts, the last of which was in Lisbon on 8 May. Two days later, after a heart attack, she underwent surgery at a local hospital in Paris. On the morning of 11 May 2010 she was taken off artificial pulmonary ventilation, and on 16 May she was discharged from the intensive-care unit and transported to a clinic for further treatment. In late September 2011, Évora's agent announced that she was ending her career due to poor health.[9] On 17 December 2011, Évora died in São Vicente, Cape Verde, at the age of 70 from respiratory failure and hypertension. A Spanish newspaper reported that 36 hours before her death she was still receiving people—and smoking—in her home in Mindelo.[10]

Awards and honors

In 1997, Évora won the KORA All African Music Awards in three categories: "Best Artist of West Africa", "Best Album", and "Merit of the Jury".[15] She went on to win ""Merit of the Jury" a second time.[16] She won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary World Music Album in 2003.[2]: 92

Évora was made an ambassador of the World Food Programme in 2004, and she was declared a cultural ambassador by the government of Cape Verde and granted a diplomatic passport.[2]: 92 She received the Grand-Cross of the Order of Prince Henry in 1999,[17] and was awarded the French Legion of Honour in 2009.[2]: 92

Musical style and image

Évora performed morna, a Cape Verdean genre of music inspired by Portuguese fado with elements of blues, among other musical styles.[1][2]: 84 Critics also identify musical traditions such as chanson and habanera as influences.[4]: 62 She picked up several nicknames during her career, including the Barefoot Diva, Cize, and the Queen of Morna.[6] Évora's songs are often sentimental in nature, and she described her music as being about "love relationships".[1] Many of her songs also cover topics like homesickness and nostalgia, which are common themes in morna, in line with the tradition of sodade.[1][2]: 84 She sang more broadly about the life of Cape Verdeans, both at home and among its sizeable diaspora,[2]: 84 as well as the lives of historical Cape Verdeans who endured colonialism and slavery.[6]

Évora mainly sang in her native language of Cape Verdean Creole, making her one of the few prominent African musical artists who did not change her performances to a global language to increase marketability,[6] though she sometimes sang songs in Spanish and collaborated with Spanish language musicians.[18]: 73 Évora's band was led by Nando Andrade,[2]: 93 and composed entirely of younger Cape Verdean men.[2]: 86 She worked with songwriters such as Nando Da Cruz, Amandio Cabral, and Manuel de Novas. Évora's uncle, Francisco Xavier da Cruz, was a songwriter, and she performed many of his songs as well.[1] Her music has been compared to that of Edith Piaf and Billie Holiday.[1][3]

Évora was called the Barefoot Diva because she often performed without shoes, which was sometimes described as a way for Évora to honor the poor.[1][2]: 89 According to her manager, Évora once took her shoes off during a show because her feet hurt, and her fans subsequently took the shoes and filled them with tips. This was then crafted into the "barefoot diva" persona to make her more marketable in the eyes of distributors.[2]: 88 Évora insisted that there was no greater explanation, and the habit was merely a reference to her first album, Barefoot Diva, and for her own comfort.[1][2]: 89 [3]

Évora was associated with her maternal image and boubou robe.[2]: 82–83 She was also known to purchase old jewelry from those in need and wear it while she performed.[2]: 92 Évora's performances were often inspired by her roots as a bar performer: she would hold an instrumental intermission in which she sat down at a bar table in the center of the stage to smoke and drink.[2]: 86 Évora did not believe in false humility, and would say that she achieved success simply because she was a good singer.[8] She had a reputation for her frequent smoking and drinking, particularly rum.[1][6][8]

Legacy

After achieving global popularity, Évora saw herself as telling the story of the oft-forgotten Cape Verde to the world.[2]: 91 At the height of her fame, Évora was the world's most well known performer of morna.[1] Lusophone studies professor Fernando Arenas described Évora in 2011 as the most well known Cape Verdean globally.[4]: 58 Évora played a significant role in increasing the global profile of Cape Verdea and its music.[4]: 45 Her influence is especially prominent in regard to Cape Verdean diaspora musicians, who often seek to emulate her music.[18]: 69

Évora is also an influence for music artists with no connection to Cape Verde: the American singer Madonna developed an interest in Portuguese and Cape Verdean music after meeting her, which influenced Madonna's studio album "Madame X" (2019) and the subsequent Madame X Tour.[19] Belgian musician Stromae admired Évora and released the song "Ave Cesaria" in her honor in 2014.[20]

Évora has been honored on stamps[21] and on 2000 Escudos banknotes.[22] On 27 August 2019, she was honored by a Google Doodle in Canada, and some European, African and Asian nations, on her 78th birthday.[23][24][25] Cesária Évora Airport in Mindelo was named after her in 2012, and the airport's entrance features a 3-metre (9.8 ft) tall statue of her.[26] The Seine-Saint-Denis department named a new college in Montreuil after her in 2014.[27][28] Two species of fauna are named after her: a butterfly in the family Lycaenidae named Chilades evorae which is found on the island of Santo Antão, and a species of sea slug called Aegires evorae, which exists in the northeast part of the island of Sal in the area of Calhetinha.[27][29]

Discography

Évora released eleven studio albums during her career, and a twelfth was released after her death.[30][31]

- La Diva aux Pieds Nus (1988)

- Distino di Belita (1990)

- Mar Azul (1991)

- Miss Perfumado (1992)

- Cesária (1995)

- Cabo Verde (1997)

- Café Atlantico (1999)

- São Vicente di Longe (2001)

- Voz d'Amor (2003)

- Rogamar (2006)

- Nha Sentimento (2009)

- Mãe Carinhosa (posthumous album, 2013)

References

- Decker, Ed (1997). McConnell, Stacy A. (ed.). Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music. Vol. 19. Gale. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-7876-1064-X. ISSN 1044-2197.

- Martin, Carla (2010). "Cesária Évora: 'The Barefoot Diva' and other stories". Transition (103): 82–97 – via Project MUSE.

- "Cesaria Evora dies at 70; Grammy-winning singer known as the 'Barefoot Diva'". Los Angeles Times. 18 December 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Arenas, Fernando (2011). Lusophone Africa: Beyond Independence. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-6983-7.

- Moon, Tom (2008). 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die. Workman Publishing Company. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-7611-5385-6.

- Abah, Adedayo L. (25 March 2021), "African Women in Music, Theater, and Performance", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.499, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4

- Grier, Chaka V. (8 November 2017). "Shocking Omissions: Cesária Évora's 'Cesária'". NPR.

- Cartwright, Garth (17 December 2011). "Cesária Évora obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- "Cesária Évora termina a carreira aos 70" (in Portuguese). Publico.pt. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Serena, Marc (18 December 2011). "Las últimas palabras de Césaria" [Cesária's last words]. Público (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Hale, Mike (30 June 2007). "What's On Tonight: [Schedule]". The New York Times. p. 16. ProQuest 433600962.

(CUNY) Black Dju (1996) This French-language film, which has played only in festivals and on television in the United States, stars Richard Courcet as Dju, a young man from Cape Verde who travels to Luxembourg in search of his father. Philippe Leotard plays the policeman he befriends, and the cast includes the Cape Verdean singer and songwriter Cesaria Evora

- "Black Dju (1996)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021.

- Holden, Stephen (30 April 1999). "Film Review; What Do You Call a Man Who's Suddenly Rich? 'Dad'". The New York Times.

- Arenas, Fernando (2011). "Lusophone Africa on Screen". Lusophone Africa: Beyond Independence. University of Minnesota Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8166-6983-7.

- "All Africa music awards". www.koraawards.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Legendary Cape Verdean Singer Cesária Évora Honored With Google Doodle - Okayplayer". www.okayafrica.com. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas". Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Hurley-Glowa, Susan (2015). "Walking Between the Lines: Cape Verdean Musical Communities in North America". The World of Music. 4 (2): 57–81. ISSN 0043-8774.

- "Madonna and Maluma Perform Sultry 'Medellín' Collab with Holograms at 2019 BBMAs: Watch". Billboard. 2 May 2019.

- "Stromae : découvrez son nouveau clip Avé Cesaria [Vidéo]". Télé Star (in French). 25 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Timbres émis avec CV007.03". www.wnsstamps.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- "2000 Escudos Banknote". Banco de Cabo Verde. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Marsh, Michael (27 August 2019). "Who is Cesária Évora? Google Doodle pays tribute to singer". nechronicle.

- "Five things to know about Cesária Évora". The Independent. 27 August 2019.

- "Cesária Évora's 78th Birthday". 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Aeroporto de Cabo Verde recebe o nome de Cesaria Évora". Pop & Arte (in Brazilian Portuguese). 9 March 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Tubei, George (27 August 2019). "Cesária Évora, Africa's "Barefoot diva" whom Google has honored". Pulselive Kenya.

- Lebelle, Aurélie (29 August 2014). "Montreuil: le collège Cesaria-Evora est prêt pour la rentrée". Le Parisien (in French).

- Msemo, Mweha (2 July 2018). "Cesária Évora: The Cape Verdean 'Barefoot Diva' honoured internationally for her music". Face2Face Africa.

- "Discography". Cesária Évora. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- "Mãe Carinhosa, Cesária Évora's Posthumous Release by Oscar Montagut - August 19, 2014". 19 August 2014.

Further reading

- Sieradzińska, Elżbieta (2015). Cesaria Evora. Minsk: Wydawnictwo Marginesy. ISBN 978-8-3647-0029-3.